Do We Really Hold Tension in Our Hips?

The Surprising Connection Between the Psoas, Emotions, and Stress

Margaux Loyer

6/27/20256 min read

Do We Really Hold Tension in Our Hips?

The Surprising Connection Between the Psoas, Emotions, and Stress

I used to be skeptical when people said things like “we store emotions in our hips.” It sounded a bit too mystical, too abstract. Do we literally stock emotions in a muscle? If emotion is a chemical, would we find fear molecules stored in our hip flexors? Well… not quite — or at least, we haven’t proven that. But the more I learned about the psoas muscle — especially through work like Liz Koch’s The Psoas Book — the more I began to understand why this idea resonates with so many people. It turns out there’s solid anatomical and physiological reasoning behind it.

Let’s take a closer look.

The Psoas: Your Deep Survival Muscle

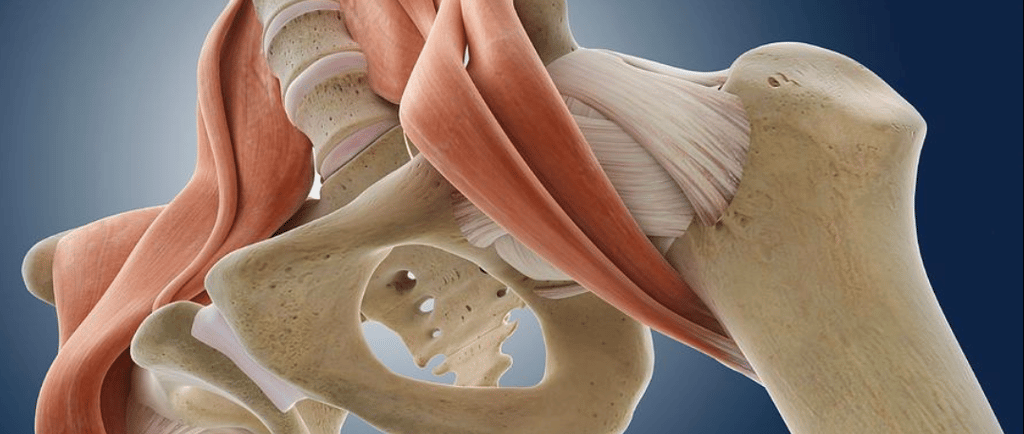

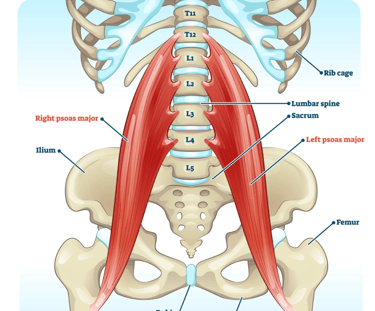

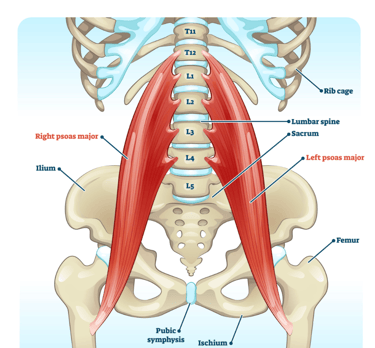

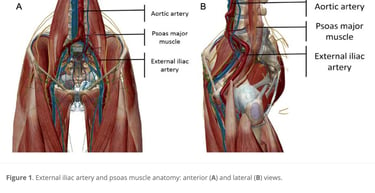

The psoas is the only muscle that connects your spine to your legs. It’s deeply embedded in the body, originating from your lumbar spine (T12–L5) and inserting onto the femur. It plays a central role in walking, running, and stabilising your pelvis and spine — making it essential for upright posture and locomotion.

But the psoas is more than a structural support. It's also deeply entwined with the nervous system. When you experience stress or fear, the sympathetic nervous system (your fight-or-flight response) kicks in. The psoas responds to this by contracting — readying the body to run, fight, or curl into a protective position (think fetal posture). This makes the psoas a key player in survival.

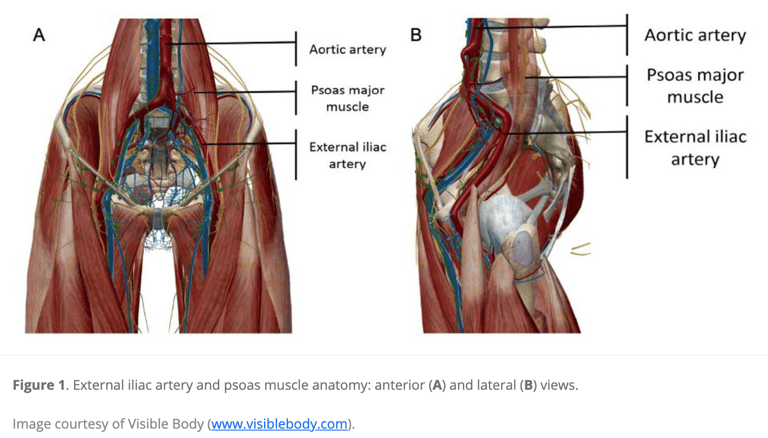

Anatomically, it sits right beside the sympathetic chain ganglia — bundles of nerves that carry stress signals throughout the body. Because of this close proximity, chronic stress can lead to chronic psoas tension. And when the stress doesn’t turn off — as is so common in our fast-paced, overstimulated world — the psoas may remain stuck in a shortened, contracted state.

Fluid Movement and Internal Circulation

The psoas acts as a hydraulic pump by moving fluids during walking or running. Its proximity to major blood vessels such as the iliac veins and iliac artery, as well as lymph nodes located in the groin area, means that the movement of the psoas gently massages the surrounding organs and supports the movement of blood, lymph, and interstitial fluids. With each step, this rhythmic compression and release keeps circulation flowing and supports the body’s internal hydration and detoxification. It’s one of the ways movement is medicine — especially when the psoas is balanced and not chronically tense.

The Breath-Stress Loop: How Psoas Tension Impacts Breathing

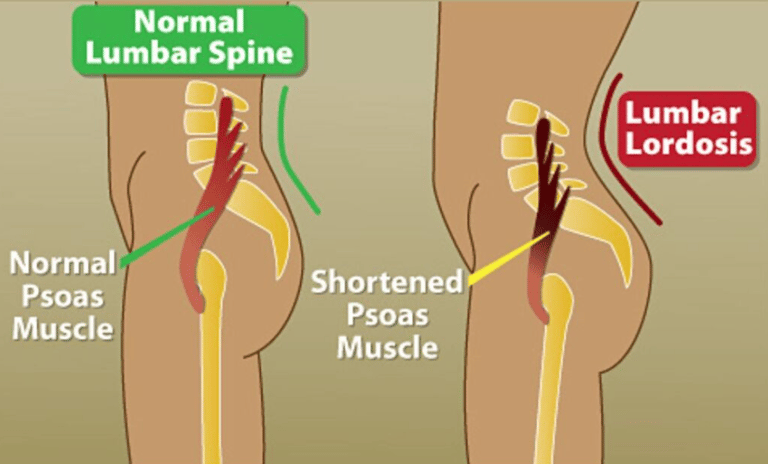

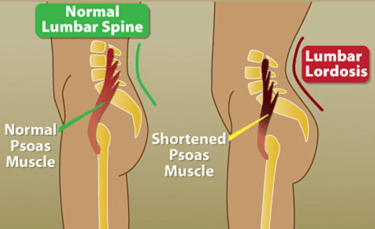

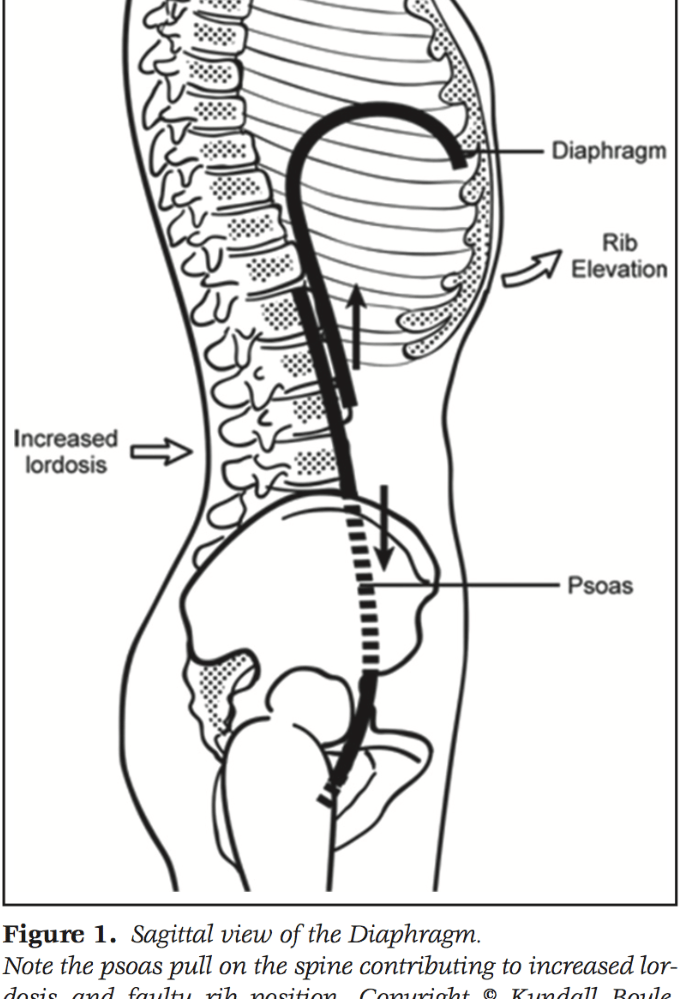

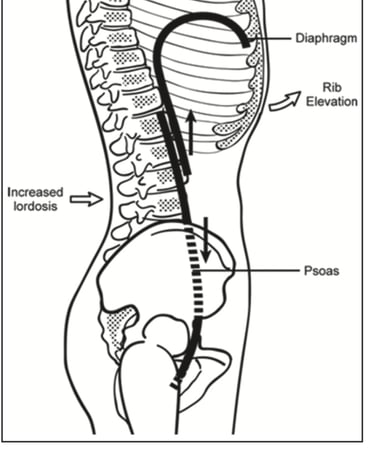

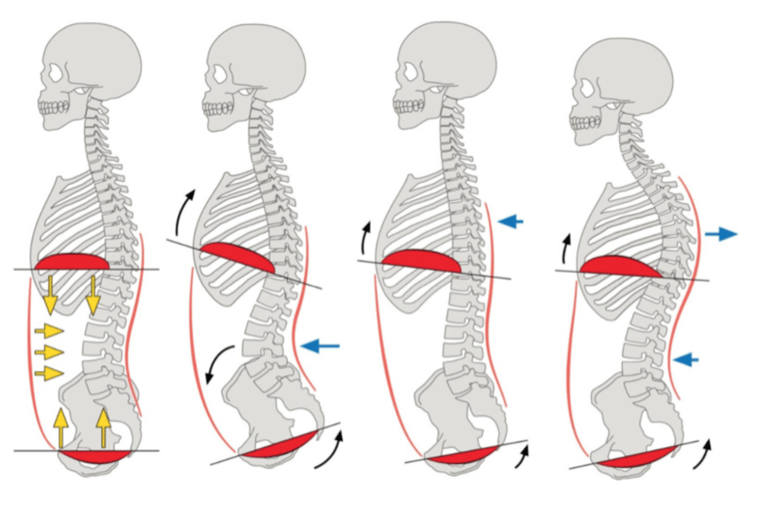

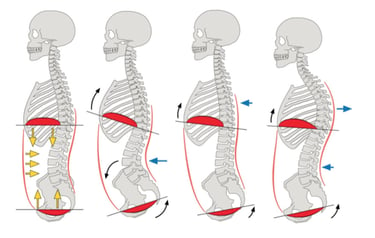

The psoas and the diaphragm — our main breathing muscle — are anatomically and functionally linked, by the crucial ligament. In fact, in dissection, they are often harder to separate from each other than the psoas and iliacus. When the psoas is tight, it can pull on the lumbar vertebrae and exaggerate the lower back’s natural arch (lumbar lordosis). This postural shift restricts the diaphragm’s ability to descend fully with each inhale.

Why does that matter? Because the diaphragm is key to activating the parasympathetic nervous system — your rest-and-digest mode. When breathing becomes shallow, we miss out on this calming effect, and the body stays stuck in sympathetic overdrive. It’s a vicious cycle: stress tightens the psoas → tight psoas restricts breathing → shallow breath reinforces stress response.

The Psoas, the Fear Reflex, and the Sympathetic Chain:

When people say we "store emotions in our hips," it might sound like poetic metaphor. But when you zoom in on the anatomy and physiology, it starts to make real sense.

The psoas isn’t just a postural muscle — it’s deeply wired into our nervous system. Anatomically, it sits right beside the sympathetic chain ganglia — bundles of nerves that run alongside the spine and relay stress signals throughout the body. These ganglia are part of the autonomic nervous system and are key players in the fight-or-flight response. Because they lie in such close proximity to the psoas, it’s easy to see how this muscle can be directly affected by chronic nervous system activation.

And here’s where it gets even more interesting: the psoas is the only muscle that connects the spine to the legs, which makes it essential for running and survival. In an emergency — whether real or perceived — this muscle is one of the first to engage. It helps us run, curl up, freeze, or brace. That’s why author Liz Koch refers to it as the "muscle of the soul" and talks about the fear reflex — a deep, primal pattern of curling inward for protection.

So, do we literally have fear chemicals stuck in our hip flexors? No. We haven’t proven that. But fear is a physiological state, driven by the nervous system — and the psoas is located right at the center of this system’s stress response.

In today’s world, where stress isn’t always a bear chasing us but a steady stream of emails, noise, and social pressure, the sympathetic nervous system can be in constant overdrive. That chronic activation doesn't just affect the mind — it impacts the body too. And the psoas, living so close to the sympathetic ganglia, often mirrors that over-activation with deep, persistent tension.

Over time, this can manifest as:

Lower back or pelvic pain

Digestive issues (from both its anatomical relationship to the gut and the effects of nervous system imbalance)

Breathing restrictions

Menstrual discomfort or fatigue

A healthy, relaxed psoas supports ease of movement, emotional resilience, and fluid breathing. A tight psoas may reflect — and perpetuate — a state of inner tension.

Leg Imbalance, Pelvic Misalignment, and Downstream Issues

When the psoas is chronically tight on one side, it shortens and pulls the spine and pelvis out of alignment. This can lead to imbalanced weight transfer during walking or running — affecting your gait and increasing the risk of compensation patterns in other muscles and joints. Over time, this asymmetry can contribute to issues like:

Hip or sacroiliac joint pain

Knee pain due to misaligned tracking

Uneven leg length or walking pattern

While not all knee, hip, or back pain stems from the psoas, it is certainly a muscle worth evaluating — and supporting — when addressing chronic imbalances in the lower body. Taking care of the psoas can go a long way in promoting harmony in the pelvic cavity, spine, and legs.

From Anatomy to Energetics: The TCM Perspective

In my view, in Traditional Chinese Medicine, the psoas area corresponds to several important energetic concepts:

Kidney Qi, which is linked to fear, vitality, and survival

Liver Qi stagnation, related to tension and emotional repression

The Chong Mai (Penetrating Vessel), an extraordinary meridian tied to reproductive health, trauma, and deep-rooted patterns

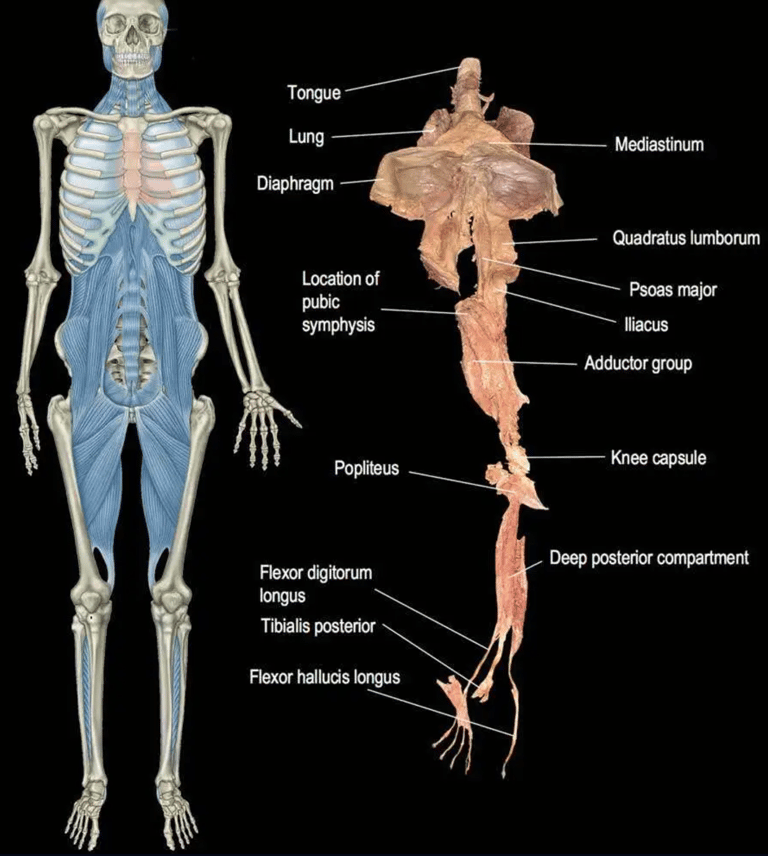

The deep fascia chain which the psoas belong to, starts at the foot, and connects to the inner thighs, pelvis, psoas, diaphragm, heart, and all the way to the tongue echo the pathways of the kidney meridian, the organ linked to the Fear and survival in TCM. It’s no wonder that the psoas has been called the “muscle of the soul.”

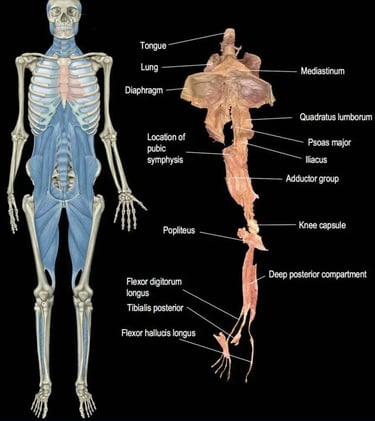

Fig. above: Deep Frontal fascia chain.

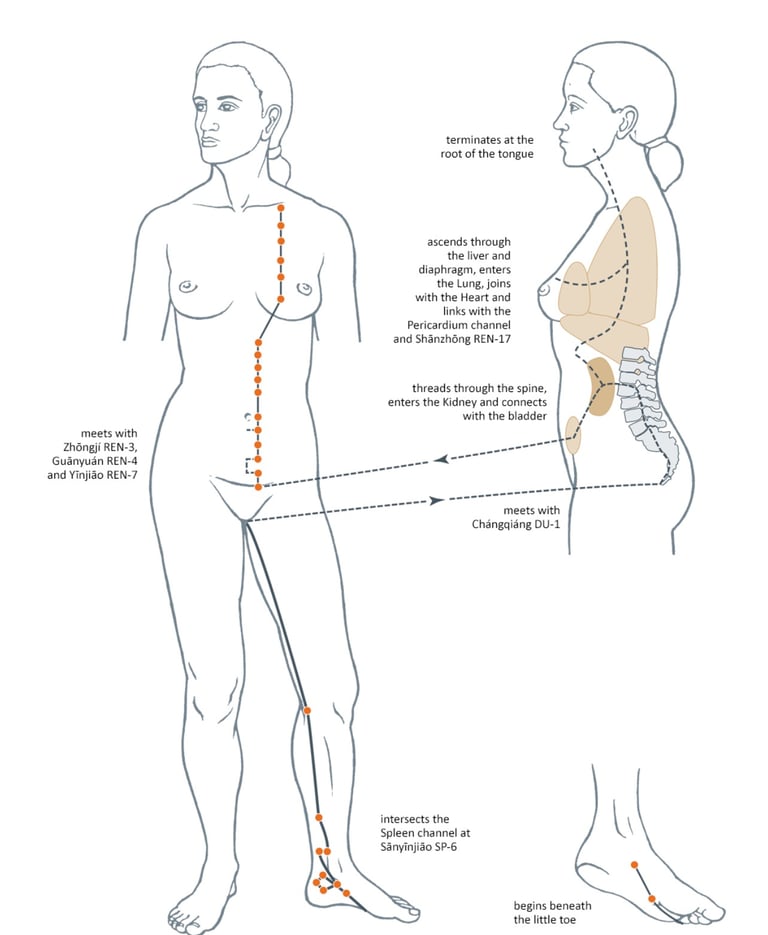

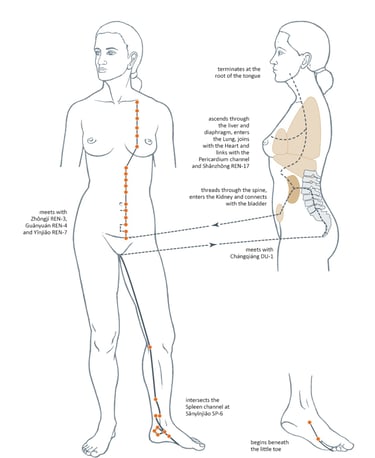

Kidney channel- starting at the feet, ascending along the medial line of the leg, all the way up through the lower spine, connecting the pelvic area, and up to the tongue.

Caring for Your Psoas

While stretching can help, true psoas release often involves more than just lengthening — it requires calming the nervous system. Practices that invite safety and deep diaphragmatic breathing (like restorative yoga, acupuncture, meditation, or gentle movement).

A few practices to explore:

Low Lunge Stretch

Step one foot forward into a lunge, lower the back knee, gently press hips forward without arching the back.

Reclined Stretch at the Edge of a Bed

Lie back, hug one knee to your chest, let the other leg gently hang off the edge to open the front of the hip.

Before doing any stretches, please consult with your health practitioner to see if it is suitable for you at this stage.

Final Thought

We may not store emotions like files in a cabinet, but our body — and particularly the psoas — reflects how we have lived, adapted, and survived. Taking care of your psoas is about more than mobility. It’s about breath, posture, resilience, and creating space for calm.

As Liz Koch says, “The psoas is not just a muscle — it's a messenger.”

Let’s start listening.

Reference

Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, Romani WA. Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Koch L. The Psoas Book. 2nd ed. Felton, CA: Guinea Pig Publications; 1997.

Rolf IP. Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well-Being. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 1977.

Staugaard-Jones JA. The vital psoas muscle. North Atlantic Books; 2012.

Restore Your Rhythm · Move With Ease

Find me At Topnotch Bodywork in West Auckland

© 2025. All rights reserved.

4/402 Don Buck Road, Massey

09 212 8753